It’s time to go whomping some dodgy statistics again, and our target for today is one that’s starting to crop up pretty regularly in commentaries on UK abortion law. You’ll find it in this fairly recent Guardian article by Caroline Criado-Perez:

Polls show 62% of the British public support abortion on demand – that is, where a woman would not have to convince two doctors that her mental or physical health would be harmed by continuing with her pregnancy. Abortion on demand would mean that an adult woman is trusted to know what is best for her body.

And it’s more or less repeated in this New Statesman article by Helen Lewis, who gives rather more information on the source she’s relying on:

Yet despite the latest British Social Attitudes survey finding that two-thirds of us support abortion if a woman “does not wish to have the child” – in effect, abortion on demand – parliament is unlikely to be receptive. Because of what O’Brien calls a “noisy minority”, and because evangelical Christians have seized on the issue, “being pro-choice is seen by some MPs as dangerous – it’s putting your head over the parapet”.

What we have here is a prime example of a statistic which is both genuine but at the same time deeply misleading or, to put it another way, what the public says when it’s asked an and pretty generic question about access to abortion is not the same as what they say when they’re asked for their views on abortion is more specific terms.

The statistic to which both Caroline and Helen refer comes from the 30th edition of NatCen’s British Social Attitudes Survey, which was published in 2012, and a report on its findings on attitudes to abortion which states:

The British Social Attitudes survey has asked a number of questions about abortion over the past 30 years. Here, we focus on two that represent the extremes at either end of the debate. Both focus on the acceptability or otherwise of abortion under particular circumstances, without broaching the issue of weekly limits. The first puts forward a situation that is clearly covered by the current Abortion Act – that a woman whose health is seriously endangered by her pregnancy be allowed to have an abortion. The second puts forward a more stretching scenario, one which is not in itself currently covered by the Abortion Act:

Do you think the law should allow an abortion when…

…the woman’s health is seriously endangered by the pregnancy?

…the woman decides on her own she does not wish to have the child?

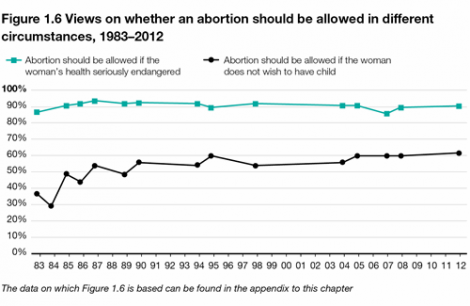

Responses to these questions are presented in Figure 1.6. They show almost unanimous support for a woman’s right to have an abortion if her own health would be seriously endangered by going ahead with the pregnancy. Nine in ten people (90 per cent) agree with this view in 2012, barely changed from the 87 per cent who agreed in 1983. However, levels of support for abortion in the circumstances set out in the second question are lower, with just over six in ten (62 per cent) supporting and a third (34 per cent) opposing. However, this marks a considerable change since 1983; at that time 37 per cent thought the law should allow this while just over half (55 per cent) thought it should not. In other words, just over half of the public in 1983 opposed abortion being available if a woman does not want a child, while nearly two-thirds support this now.

Figure 1.6, which is referred to in that passage, looks like this:

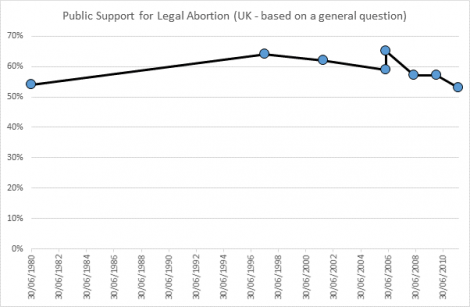

So this is certainly a genuine statistic and one that, at least from the late 80s onwards, is closely mirrored in polls undertaken by the polling companies Ipsos Mori, Comres and Angus Reid on behalf of Bpas, Marie Stopes International and the Sunday Times – and even, in one notable case, in a poll by Comres that was commissioned by an anti-abortion group.

So this is certainly a genuine statistic and one that, at least from the late 80s onwards, is closely mirrored in polls undertaken by the polling companies Ipsos Mori, Comres and Angus Reid on behalf of Bpas, Marie Stopes International and the Sunday Times – and even, in one notable case, in a poll by Comres that was commissioned by an anti-abortion group.

What all these polls have in common is that they asked the public for their opinions on abortion in purely generic terms, such as whether they think abortion should be legally available to all who want it or whether, if a women wants and abortion she should not have to continue with her pregnancy or, in the case of the Comres poll, whether people agree that “a woman’s right to choose always outweighs the rights of the unborn” – and if you that kind of question then anything from 55% to 65% of a representative sample of the British public will reply by saying that, yes, women should have to continue a pregnancy if they don’t want to.

But what if you don’t just ask a general question? What happens when you ask people for their views on specific issues and scenarios?

Well then the polling starts to look rather different.

In 2014 Comres ran two polls, both commissioned by anti-abortion groups (the Christian Institute and Christian Concern) which asked the public about their views on abortion solely on the grounds of the gender of the foetus and in both poll over 80% of those surveys (86% in the Christian Institute poll, 84% in Christian Concern poll) agreed that abortions carried out solely on the grounds of the gender of the foetus should be explicitly prohibited in law.

In a 2006 poll, also by Comres, 71% of those surveyed agreed with the proposition that “fathers should be given a say over whether their child is aborted” – although how much of a say and whether that extends all the way to a veto isn’t specified – while 54% said that they think it is unacceptable that UK law allows abortions on the grounds of “disability” up to the point of birth.

Also on the subject of foetal abnormality, polling carried out by Ipsos Mori back 1980 showed that 84% of the British public approved of abortions carried out on the grounds of “mental handicap or mental disability) with 81% approving of abortions carried out on the grounds of physical disability. By 1997, when Ipsos Mori carried out a poll containing similar questions on behalf of Bpas only 67% of those polled said they approved of abortions carried out of the grounds of “serious learning difficulties that used to be known as ‘mental handicap’” while just 66% approved of abortions on the grounds of “serious physical disabilities”. It wasn’t just the language that changed in the seventeen years between 1980 and 1997, so did public opinion and contrary to the usual pattern one finds in abortion polls in which older people tend to be more conservative in the views on abortion, the big shift in public opinion on this issue to be found amongst young people where the 1997 poll indicated that only 50% of people under 25 approved of abortion on the grounds of a foetal abnormality that would leave a child, if born, with serious learning difficulties while 40% said they approved of abortion where a foetus otherwise be born with a serious physical disability if carried to term.

Bpas and Ipsos Mori ran the same poll again in 2001 and 2006 and across both polls public approval of abortion on the grounds of a serious physical disability remained broadly the same – it actually rose to 70% in 2001 but dropped back to 64%, only slightly below the 1997 figure, by 2006. However when it came to abortion on the grounds of abnormalities that would give rise to a serious learning disability the downward trend observed in the figures for 1997 continued with public approval for such abortions falling to 64% in 2001 and just 55% by 2006. If that trend has continued on the same trajectory in the nine years since the 2006 poll then public support for abortion on the grounds of a foetal abnormality that’s known to cause serious learning disabilities will have dropped below 50% and will probably come in, today, at somewhere around 47%.

Then there’s the question of the upper time for elective abortion on grounds other than those of the pregnancy posing a serious risk to the life of the mother or a serious foetal abnormality, which was set at 28 weeks gestation by the 1967 Abortion Act and revised in 1990 down to 24 weeks except for abortions on the grounds of disability where the upper limit was set effectively at any point up to birth.

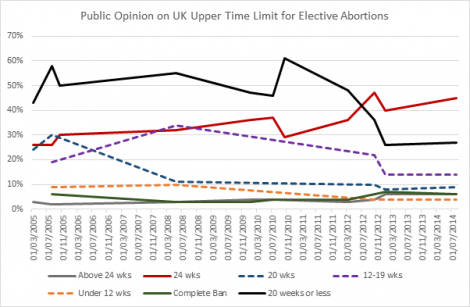

On that issue, I’ve managed to dig out eleven polls spanning the last ten years in which a specific question was asked about the upper time limit and the public views on whether it needed to changed and the overall trend from those polls looks like this:

So, if we take that graph at face value then it would appear that public support for the current 24 week limit has strengthened over the last five to seven years while support for a reduction in that limit has fallen away considerably since 2010. However that’s not quite the full story here and the key to understanding at least part of what’s been going on with public opinion on the 24 week time limit lies in what appears to be a sudden, if rather short-lived, drop in support for that limit – and a parallel increase in support for a reduction below 20 weeks – across two polls conducted only three months apart in 2010.

The earlier of these two polls was conducted by Angus Reid and used this relatively neutral question:

In Great Britain, it is only legal to have an abortion during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, provided that certain criteria are met. Thinking about this, which of these statements comes closest to your own point of view?

The statements from which those taking the survey could choose enabled them to indicate whether they wished to see the upper time limit increased, decreased or whether it should stay the same and although the most popular option was a decrease in the time limit (47%), 37% of those surveyed said they thought the 24 week limit should stay the same.

Three months later Comres carried out a poll on behalf of Christian Concern which asked whether the people being surveyed would support a reduction in the upper time limit to 20 weeks or less and in that poll only 29% said they’d prefer to stick with the 24 week limit while support for a reduction in that limit to 20 weeks or less came in at 61%, the highest figure for any poll on this specific issue in the last ten years.

The major difference between the two polls lies in part in the wording of the question used in the Comres poll, which asked whether people would support or oppose a series of possible changes to abortion law, including a reduction in the upper time limit, but mostly in the way that this poll used two questions which were asked before people were to give an opinion on the upper time limit to set up for that question.

The first of these two questions asked to estimate how many abortions were carried out in Britain each year and gave a range of options which ran from 0-20,000 all the way up to over 500,000. The actual figure at that time was little over 200,000 a year for England, Wales and Scotland combined and only 3% of those surveyed gave an answer in the right ballpark; 1% said 200,001-250,000, which was the correct figure, while 2% said 150,001-200,000, which was slightly under the true figure but an answer that people who at least knew that the correct figure for England and Wales was around 195,000 might easily give if they forgot take into account Scotland, which publishes it’s figures separately. Of the remaining 97%, only 7% overestimated the annual number of abortions, 49% underestimated this actual figure with 30% guessing that it was less than 20,000 a year and remaining 41% just gave up and said they didn’t know.

The second question gave the actual figure – just over 200,000 – and then asked people whether they though this figure was too high and that ways should be found to reduce or whether it was a reasonable figure which meant that no action needed to be taken, and because most of the people who were surveyed either significantly underestimated this figure when they were asked the first question or just said they didn’t know inevitably 61% agreed that the figure was indeed too high and ways should be found to reduce it; almost exactly the same number of people who then went on to say that they agreed that the upper time limit should be reduced to 20 weeks or less when that question was put to them – the percentage figures are the same due to rounding but difference between the actual figures for each question as just 10 people out of the 1,003 that were surveyed.

What I’ve described is a practice called “priming” in which – in the context of opinion polls – the people taking part in the poll are fed additional information either within a question itself, or through other questions asked immediately prior to the key question(s) in the poll, specifically to try and bias the outcome of the poll in a particular direction and in the polling on the upper time limit for abortion this has been a pretty effective tactic. Of the eleven polls in the dataset from which the graph showing public opinion on the time limit was generate, five included additional non-neutral information within either the question which asked for people’s opinions on the 24 week time limit or in questions leading up to that question, including the four earliest polls in the dataset which span the period from 2005 up to May 2008 and the vote that took place in the House of Common on a series of amendments which sought to lower that time limit to anything from 12 weeks to 22 weeks gestation and the difference between results of the primed and unprimed polls is significant. On average, public support for the existing 24 week limit is 11 percentage points higher in the polls that used only a neutrally worded question than in the polls that set out to prime people in favour of a reduction in that limit while support for a reduction in that limit to 20 weeks or less was 15 percentage points higher in the polls that used priming. Unsurprisingly, three of those five primed polls were commissioned by anti-abortion organisations while the other two were commissioned by the Daily Telegraph.

So all those primed polls are unreliable, yes?

Well, not necessarily.

Priming is one of those issues that raises some interesting and rather difficult epistemological and methodological questions within the field of social sciences not least in terms of the ecological validity of research findings.

Priming introduces an element of bias into survey-based research findings but that may not be a problem if the biases that it introduces are ones that closely reflect biases that exist in the real world when people are required to response to questions in circumstance in which their answer matters and they take the time to think carefully through their response before they give it. At the last UK general election, the political polling right up to election day proved to be badly out of line with how people actually voted on the day and of the reasons put forward to explain, and one I certainly think is plausible, is that the carefully designed, neutrally worded, questions on voting intentions used by polling companies failed to prompt people to think about how they intended to vote in the same manner that they actually thought about it when it came to actually making a mark on a ballot.

As such, we can certainly discount one of the polls in that data set as unreliable – not because it used priming but because it primed survey respondents with patently false and misleading information – but not necessarily all of the others. In some cases the priming statements may simply have prompted people think about issues they might very have taken into account were they, for example, voting on changes to abortion law in a referendum, such the poll offers a somewhat more accurate reflection of what public opinion would look like in that situation.

The last poll I want to look at for now was conducted in 2008 by Ipsos Mori on behalf of Marie Stopes International and it’s of particular interest and relevance because, somewhat unusually, it include both a general question on public attitudes to abortion and a question on a specific issue.

In that poll, 1032 women aged between 18 and 49 were first asked about the extent to which they either agreed or disagreed with the proposition that women should have the right of access to an abortion, and in keeping with the public response to general questions in that vein in other polls 57% of those surveyed either agreed or strongly agreed that women should indeed have that right.

The poll then went on to ask this question:

Abortion is currently legal within 24 weeks. That is, a woman is allowed to have an abortion at any time within the first 24 weeks of her pregnancy, when two doctors have agreed that the abortion is in the interests of her physical or mental health. A very small proportion of abortions (fewer than 2 in one hundred) take place between 20 and 24 weeks. There is currently a debate about the legal time limit. In which, if any, of the following circumstances do you think a woman should have the right to access an abortion between 20 and 24 weeks? You may select more than one option.

So here we’re looking specifically at people’s view on late-term abortions carried out close to the current 24 week upper limit and the headline finding of the poll was that 61% of the women who were surveyed decided either that at least one of the eight options that were put up for consideration in the question did describe a situation in which they though a woman should be able to get a late-term abortion (57%) or that woman should have that right regardless of their circumstances (4%).

So far, so good – but then we get to the detailed results for each option for which the figures were:

| Foetus diagnosed with severe abnormalities | 40% |

| Conception due to rape | 38% |

| Pregnancy places the woman’s health at risk | 37% |

| Woman has an abusive partner | 16% |

| Request for abortion delayed by doctor | 15% |

| Woman did not realise earlier that she was pregnant | 13% |

| Woman was young and was in denial or early signs of pregnancy | 6% |

| Woman’s partner left her during the pregnancy | 6% |

All of which means that of the 57% of women who agreed that women should have a right to access an abortion, 17% don’t consider that that right extends as far as aborting a foetus with a severe congenital or developmental abnormality once it reaches 20 weeks gestation, 18% don’t view that right as being one which should be extended to women who became pregnant after they were raped but didn’t, for whatever reason(s), sort out an abortion earlier in the pregnancy and 20% think than once the pregnancy gets to 20 weeks then women just put up with any health risks it generates until they give birth.

So what is all additional polling telling us?

Well, first and foremost, that a sizeable proportion of British public have neither strong ideological views nor a carefully thought through and reasoned position on abortion in which they’ve consider most or all of the many complex ethical questions that can arise in different situations when a request for an abortion is made. What the polls reflect is not so much what people think abortion but, in many cases, what they feel and how many people say they feel depends very much on precisely which questions you ask, how you ask those questions and the extent to which people are primed with certain types of information before you ask, either by the survey itself or by information that’s being provided by the media at around the time you run the poll.

Put simply, although around 60% of the public will say that women should generally have the right to terminate a pregnancy that apparent support for abortion rights become very heavily qualified when you ask about specific situations in which women might actually request an abortion. Public perceptions of abortion are shaped primarily by the view that abortion is, to varying degrees, a necessity rather than freely exercisable right.

So, bearing all that mind, what proportion of the British public is actually likely to support full decriminalisation on the terms proposed in Caroline Criado-Perez’ article?

Currently around 4-5%, given that decriminalisation would amount to the legalisation of abortion in any circumstances and for any reason up to the point of birth and that only around 4-5% of the public have consistently said they would support any kind of extension to the current 24 week limit over the last ten years.

That’s roughly the same figure as the percentage of the British public who would support an outright ban on abortion in all circumstances, although there there’s around another 8-10% who would back the prohibition-lite version under which makes concessions for abortions where there the pregnancy creates a serious risk to the woman’s life and where conception was due to either rape or incest.

That’s the actual baseline level of current support for full decriminalisation and it’s a long way short of the 62% figure that’s being bandied around on the back of the NatCen survey results, which fall a very long way short of offering a clear and accurate picture of the public’s view on abortion.

I hate to be the bearer of bad tidings but there are signs in some quarters of a severe outbreak of naivety in some quarters, driven to some degree on the back of the success of the Irish referendum on same-sex marriage, but the truth are that the British public do not feel the same way about the two issues. Public support for the legal availability of abortion is much more heavily qualified that it was for same-sex marriage, where 54% said they backed legalisation in the final YouGov poll on the issue before the House of Commons voted on the issue in 2013, as very quickly becomes evident if you look at all the polling data rather just cherry-pick the statistic(s) that most suit your personal position.

I think you’re utterly wrong about priming here, both in terms of poll ethics and as a factor in GE15 (where it’s clear that poor sampling of over-70s was the issue). People are ignorant and remain so, and any attempt to pretend that the public are informed on any issue, referendum or no, is deeply stupid.

I’ve often wondered about polls on abortion how often people are answering the question “Should a woman have an abortion in situation X?” rather than the question “Should a woman be allowed to have an abortion in situation X?”.

For instance, I’d hold that women should not have an abortion on grounds of foetal disability, but should be allowed to.

I’ve never seen an opinion poll that separated those two questions out explicitly, and a question of whether you “approve of an abortion under particular circumstances” could easily be take as a question of whether you think the woman made the right choice, rather than a question of whether you think she should have been allowed to make the choice.

I’d love to see a pollster do a collection of circumstances and say something like “For each of the following circumstances, say whether you think it is right or wrong to have an abortion for that reason, and then, separately from whether you think it’s right or wrong, whether you think it should be legal or illegal” – and then the shopping list.