Okay, I’m going to keep this short and sweet because I’m working on something else at the moment but there a little something that I want to toss into the growing online debate about the “Saatchi Bill” or, to give its proper title, the Medical Innovation Bill.

The back story here, if you’ve not come across it before, starts with the death, in 2011, of the author Josephine Hart the cause of which was primary peritoneal cancer. Hart was married to the wealthy PR guru and Conservative peer Maurice Saatchi and it is as a member of the House of Lords that Saatchi is seeking to introduce a private Bill which he claims which he, his supporters and a slick and well resourced PR machine claim will remove a supposed legal barrier to innovation in medical research and speed up the search for a cure for cancer by giving researchers legal immunity if they speculatively try out new and unproven treatments on seriously ill patients.

This all sounds peachy, if you listen only to what the Saatchi PR team have to say about the Bill, which they claim is only opposed by lawyers who specialise in medical negligence claims but the reality is that this is some considerable way from the truth given what a wide range of professional bodies and patient organisations had to say in response to a recent Department of Health consultation:

We have been unable to find evidence that fear of medical litigation is currently a barrier to innovation in cancer. (Cancer Research UK)

The RCP does not have significant evidence (anecdotal or through case examples) from our members and fellows, nor we understand do two medical protection organisations, that litigation or potential litigation is a substantial or primary deterrent to clinicians’ use of innovative treatment. (Royal College of Physicians)

However, at present, we do not believe the wording of the Bill achieves [the aims of the bill]. In particular, we have a concern that it could protect doctors deviating in a harmful way from standard practice…

A doctor should not be allowed to simply disregard a body of clinical opinion or colleagues in their multi-disciplinary team. (Royal College of Surgeons)

No, we have no evidence that doctors are deterred from innovation by fear of litigation. (Royal College of Radiologists)

The Academy and medical Royal Colleges are not persuaded that the Bill will achieve its stated purposes and we are concerned that it could have unintended adverse consequences…

We have not seen any evidence that suggests litigation or the possibility of litigation is deterring clinicians from innovative practice and, anecdotally, that is not the experience of members. (The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges)

The Bill is concerned with medical innovation yet does not itself deal with the conduct of research. We feel that innovation and research are intimately linked since innovation requires an evidence base if it is to be put into practice, which is unachievable using data obtained from a single patient (or a small number of patients). (Academy of Medical Sciences, Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust)

The BMA strongly believes that this Bill should not become law and, for the reasons outlined in this response, does not believe that primary legislation which focuses on redefining clinical negligence is the best mechanism to promote or encourage responsible innovation, should there be a need to do so, when other more suitable alternative approaches exist. The draft Bill is therefore unnecessary, risks removing important protections for patients and could encourage reckless practice, with attendant risks for patient safety. (The British Medical Association)

It is the bedrock of medical ethics that treatments must be both safe and efficacious, and these principles serve well to strike a balance that allows scientifically proven new treatments to be promoted without making it easy to exploit vulnerable people with a serious illness. We fear that the provisions of this Bill could undermine this position, and unintentionally open the door to the exploitation of people with MND. (Motor Neurone Disease Association)It increases the risk to vulnerable patients of mavericks with irrational or unjustifiable grounds for proposing a treatment and those with commercial interests in promoting dubious treatments…

The assessment suggests there will be a reduction in medical negligence claims. On the contrary there is likely to be protracted and complex litigation about the meaning of this Bill. (Robert Francis QC, author of the two Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust enquiries)

It suggests that doctors should take account of the opinions of ‘those doctors who they wish to’, and places on them no obligation to take account of the opinions of doctors who have relevant clinical expertise in the area. As currently drafted, this addition removes an important safeguard for patients by removing a key requirement of responsible practice. (General Medical Council)

And there are many comments in the same vein where those came from…

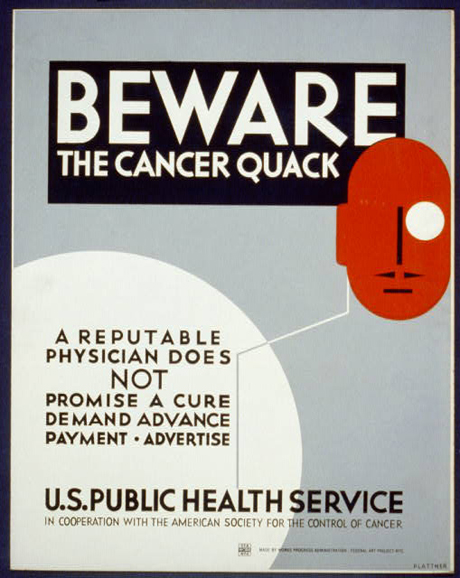

So what we have is a large body of professional opinion which states, quite clearly, that the Bill not only sets out to fix a “problem” that doesn’t actually exist but that it could also quite easily undermine legitimate medical research and create what amounts to a “Quack’s Charter” but this is still, of course, opinion so the question I asked myself is whether there might be a ready source of evidence that might help people to adjudicate between these competing claims and the answer to that question is “Yes”.

You see, if you head over to the website of NICE, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and take a bit of poke around what you’ll eventually run into is a section that provides access to all the technology appraisals that the organisation has carried out since it was created in 1999. These appraisals are a key part of the process that all new treatments have to go through before they’re approved for use in the NHS, the part where NICE looks in detail at the evidence which shows whether or not a new treatment is effective, what kinds of benefits it has to offer patients, how all this compares to any existing treatments and what it costs to provide that treatment. Once its done all then then NICE will make a recommendation as to whether or not NHS doctors should use that treatment and, if so, which which patients in which situations.

It’s a complicated and occasionally controversial process but for our purposes it provides a certain amount of useful information and evidence because the database of technology appraisals shows how many different treatments have been put forward for assessment and approval over the last fourteen years and the conditions they relate to, giving us a rough but useful idea of which conditions, diseases and illnesses are attracting the most attention from researchers. Think of it as a rough guide to the current state of play in medical innovation, there more appraisals there are for treatments relating to particular condition the more research there is likely to be relating to that condition, etc. so if there are any significant barriers to innovation in, say, developing new cancer treatments compared to developing treatments other serious conditions then this may be evident in the figures.

So, if we look just at the list of appraisals that NICE have carried out we find that there are 313 on the list.

Not all of these were successful by any means. There are some which resulted in NICE recommending that a particular treatment should not be used by the NHS because it proved to be less effective than other existing treatments or because although it offered some benefits over current best treatments these weren’t enough to justify the additional costs of the treatment. There are also some treatments in there that were initially approved but which have been withdrawn after problems were found once it had reached the market, some which were initially turned down by NICE but then approved after being resubmitted with better evidence and revised costs and some that were pulled during the appraisal process as a result of new trial data providing evidence of problems that weren’t apparent when the application for approval was originally made.

Nevertheless, it remains the case that out of the 313 appraisals, 11o (35.1%) were related to the treatment of cancer. About half-a-dozen of these were for adjunct treatments designed to tackle some of the side effects of certain types of chemotherapy and there are a fair few examples of new drugs being submitted more than once as drug companies sought approval for use with different type of cancer but the fact is that over the last fourteen years NICE has carried out just over four times as many appraisals relating to the treatment of cancers than it has for the next most ‘popular’ condition, which is arthritis and five times as many appraisals for cancer treatment than it has treatments for heart problems (e.g. CHD, angina, etc.).

In fact, if you add to together all the appraisals carried out over the fourteen years relating to treatments for heart conditions, arthritis, skin conditions such as psoriasis, dermatitis and eczema, diabetes, asthma, degenerative conditions affecting eyesight, neurological disorders and psychiatric conditions you’ll still come up seven short of the number of cancer-related appraisals.

Those figures don’t appear to suggest that there are too many legal barriers affecting research into new cancer treatments and that just the stuff that NICE have actually done. They also have a list of 155 applications which are currently being prepared for assessment of which 69 (44.5%) are either new cancer treatments, and again that includes application to expand the range of cancers for which some drugs which have already been approved can be used.

If nothing else, those figures tend to suggest that if progress towards curing cancer is rather slower that Maurice Saatchi might like then its certainly not for lack of effort on the part of the research community nor does it suggest that this research is running up against any significant legal obstacles, in which case why try to ‘fix’ a system that isn’t broken, least of all in a manner which could very easily open to the door to cancer quacks.

2 thoughts on “What Saatchi Doesn’t Tell You”