I want to return to the High Court judgment in Bell v Tavistock and take a closer look at one of the more contentious issues that was put before the court, this being the question of the exact purpose for which puberty blockers are prescribed to adolescents presenting with Gender Dysphoria and the extent to which this influenced the court’s view as the full extent of issues that necessarily must be taken into account in assessing a minor’s capacity to give informed consent to their use.

If you’ve not read the full judgment, you can get a basic sense of the main points of contention from the following paragraphs:

136. Indeed the consequences which flow from taking PBs [Puberty Blockers] for GD [Gender Dysphoria] and which must be considered in the context of informed consent, fall into two (interlinking) categories. Those that are a direct result of taking the PBs themselves, and those that follow on from progression to Stage 2, that is taking cross-sex hormones. The defendant and the Trusts argue that Stage 1 and 2 are entirely separate; a child can stop taking PBs at any time and that Stage 1 is fully reversible. It is said therefore the child needs only to understand the implications of taking PBs alone to be Gillick competent. In our view this does not reflect the reality. The evidence shows that the vast majority of children who take PBs move on to take cross-sex hormones, that Stages 1 and 2 are two stages of one clinical pathway and once on that pathway it is extremely rare for a child to get off it.

137. The defendant argues that PBs give the child “time to think”, that is, to decide whether or not to proceed to cross-sex hormones or to revert to development in the natal sex. But the use of puberty blockers is not itself a neutral process by which time stands still for the child on PBs, whether physically or psychologically. PBs prevent the child going through puberty in the normal biological process. As a minimum it seems to us that this means that the child is not undergoing the physical and consequential psychological changes which would contribute to the understanding of a person’s identity. There is an argument that for some children at least, this may confirm the child’s chosen gender identity at the time they begin the use of puberty blockers and to that extent, confirm their GD and increase the likelihood of some children moving on to cross-sex hormones. Indeed, the statistical correlation between the use of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones supports the case that it is appropriate to view PBs as a stepping stone to cross-sex hormones.

So let’s clarify a few things before we get into this properly and to help with this I’ll be using information from current version of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health [WPATH] Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, this being version 7 which was originally published in 2011.

Now the first thing to note about these particular standards of care is that they can really only be considered to be guidelines at this point in time. This isn’t because of any kind of pirate code thing, its because they don’t currently meet internationally accepted standards for standards of care because they haven’t been reviewed for almost ten years and they are not currently based on any systematic reviews of the available evidence. That raises a few issues around the quality of evidence on which these guidelines are based, not least because it pre-dates the diagnostic shift from “Gender Identity Disorder” in DSM IV to “Gender Dysphoria” in DSM V, which was formally instituted in 2013.

To be scrupulously fair, WPATH does try to anticipate this change in its guidelines but it nevertheless creates some issues around the correct interpretation of older studies that use DSM-IV criteria in its evaluation of evidence. For example, there are known issues around older studies of desistance rates in children and adolescents presenting with non-congruent gender identities, for all WPATH explicitly cite only two such studies in their guidelines. Under DSM-IV it was possible for individuals to be diagnosed with Gender Identity Disorder without them actually presenting with Gender Dysphoria and that, necessarily, raises questions around the relevance to these older studies to the question of desistance rates in individuals diagnosed specifically with Gender Dysphoria under the DSM-V criteria.

While we’re broadly on the subject of statistics relating to desistance, detransition and regret, studies commonly cited by trans-activists and their supporters can be similarly problematic when it comes to children and adolescents. Perhaps the most comprehensive study to date, the Amsterdam Cohort study, does indeed report very low rates of post-transition regret in individuals who have under gonadectomy (0.6% in transwomen, 0.3% in transmen). Unfortunately, when you drill down into the detail of the study you find that the reported average time to regret was almost 11 years (130 months), so when we look at the baseline data for the cohort it quickly become obvious that, at the time the study was conducted, it was likely to be too soon to see any significant signs of regret in the vast bulk of the child/adolescent population seen by the Amsterdam Clinic.

What this illustrates, more than anything else, is the utter sterility of Twitter arguments about desistance and dettransition in which opposing camps start throwing around citations, and statistics taken from those citations, in support of their ideological positions on trans rights. What we have is people with different ideological views throwing around different statistics from different studies based on different populations at different times under different criteria for defining gender incongruity and gender dysphoria, all in the mistaken belief that whatever it is they’re citing proves the validity of their ideological position and its superiority over that of whoever they happen to be arguing with.

It doesn’t.

Anyway, let’s move on and look at what WPATH has to say about the overriding purpose of puberty suppression in the treatment of adolescents presenting with Gender Dysphoria.

Two goals justify intervention with puberty suppressing hormones: (i) their use gives adolescents more time to explore their gender nonconformity and other developmental issues; and (ii) their use may facilitate transition by preventing the development of sex characteristics that are difficult or impossible to reverse if adolescents continue on to pursue sex reassignment.

Puberty suppression may continue for a few years, at which time a decision is made to either discontinue all hormone therapy or transition to a feminizing/masculinizing hormone regimen. Pubertal suppression does not inevitably lead to social transition or to sex reassignment.

This is fundamentally the position that the Tavistock Clinic took in court and it’s a position that the court explicitly rejected based on the evidence presented to it, concluding that the assertion that pubertal suppression does not inevitably lead to sex reassignment is unsupported by current evidence. In fact it would be more accurate to say that pubertal suppression in adolescents presenting with Gender Dysphoria almost always leads to progression on to cross-sex hormones, and eventually surgery, based on the evidence the court heard, most of which was supplied by the Tavistock Clinic – notwithstanding its inability to provide the court with a full copy of its own study – and experts submitting evidence in support of the Clinic’s position.

No precise numbers are available from GIDS (as to the percentage of patients who proceed from PBs to CSH). There was some evidence based on a random sample of those who in 2019-2020 had been discharged or had what is described as a closing summary from GIDS. However the court did have the evidence of Dr de Vries. Dr de Vries is a founding board member of EPATH (European Professional Association for Transgender Health) and a member of the WPATH (World Professional Association for Transgender Health) Committee on Children and Adolescents and its Chair between 2010 and 2016, and leads the Centre of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at the Amsterdam University Medical Centre in the Netherlands (CEGD). This is the institution which has led the way in the use of PBs for young people in the Netherlands; and is the sole source of published peer reviewed data (in respect of the treatment we are considering) produced to the court. She says that of the adolescents who started puberty suppression, only 1.9 per cent stopped the treatment and did not proceed to CSH. [Bell v Tavistock, paragraph 57]

The court also received some preliminary information about the Tavistock’s own study which is to be found later in the judgement:

The Evaluation Paper on the Early Intervention Study at GIDS, referred to in para 25 above, gives some (albeit limited) material on the outcome of that study. It summarised a meeting paper presented by Dr Carmichael and Professor Viner in 2014 (but not published in a peer review journal) as follows:

“The reported qualitative data on early outcomes of 44 young people who received early pubertal suppression. It noted that 100% of young people stated that they wished to continue on GnRHa, that 23 (52%) reported an improvement in mood since starting the blocker but that 27% reported a decrease in mood. Noted that there was no overall improvement in mood or psychological wellbeing using standardized psychological measures.” (emphasis added) [Bell v Tavistock, paragraph 73]

This clearly doesn’t address the question of whether Tavistock’s study participants elected to move forward on to cross-sex hormones when this option became available to them at 16 years of age but this question was answered the day after the High Court handed down its ruling when the clinic quietly released a preprint of its own study to the MedRXIV service, at which point it was confirmed that of the 44 individuals enrolled in the study, 43 moved on to cross-sex hormones:

Results

44 patients had data at 12 months follow-up, 24 at 24 months and 14 at 36 months. All had normal karyotype and endocrinology consistent with birth-registered sex. All achieved suppression of gonadotropins by 6 months. At the end of the study one ceased GnRHa and 43 (98%) elected to start cross-sex hormones.

This is clearly a bit awkward. On the one hand, the Tavistock is going to court to argue that it only needs to base its assessment of Gillick competence on an understanding of the role and effects of pubertal suppression because this is being prescribed to give adolescents “more time to explore their gender nonconformity and other developmental issues” leaving open the possibility of desistance at some point before moving on cross-sex hormones becomes and option, as per WPATH’s guidelines. On the other hand, their own research study indicates, in keeping with the only other source of published peer reviewed data supplied to the court, that adolescents who are given puberty blockers almost always move on to cross-sex hormones.

So what exactly is going on here?

To understand this properly we need to look at the characteristics of those who took part in the Tavistock study, a study that was design to replicate the Dutch study conducted by Dr DeVries and others.

The Tavistock paper gives us, in the first instance, some basic demographic information to work with, as follows:

Participants received psychosocial assessment and support within the GIDS before entering the study for a median of 2.0 years (IQR 1.4 to 3.2; range 0.7 to 6.6). The median time between first medical assessment at UCLH and starting treatment was 3.9 months (IQR 3.0 to 8.4; range 1.6 to 25.7). Median time in the study was 31 months (IQR 20 to 42, range 12 to 59).

Baseline characteristics of the participants by birth-registered sex are shown in Table 1. Median age at consent was 13.6 years (IQR 12.8 to 14.6, range 12.0 to 15.3). A total of 25 (57%) were birth-registered as male and 19 (43%) as female. At study entry, birth-registered males were predominantly in stage 3 puberty (68%) whilst birth-registered females were predominantly in stages 4 (58%) or 5 (32%) with 79% (15/19) post-menarcheal. 89% of participants were of white ethnicity. Birth-registered females were on average 6 months older than birth-registered males at study entry.

Elsewhere in the paper we’re also told that eight of the forty-four individuals enrolled in the study, seven of whom were natal males, were initially ineligible for treatment at the point of their second medical visit due to their being insufficiently advanced in puberty at the time of the appointment leading them to experience a median waiting time of seven months prior to enrolment, although the range data indicates that one individual had to wait a little over 2 years (25.7 months) to commence treatment.

In addition to meeting basic criteria regarding age and pubertal development, the individuals enrolled in the study had to meet several other key criteria.

They had to have been in the system at GIDS for at least six months and have attended at least four assessment/therapeutic appointments, and indeed we can see the shortest period from referral to enrolment was about 8 months, although one individual had been in the system for just over six and half years before joining the trial.

The also had to have exhibited “an intense pattern of cross-gendered behaviours and cross-gender identity” in childhood, which the study defines as being over five years of age, and to have exhibited a marked increase in their symptoms of Gender Dysphoria with the onset of puberty sufficient for clinician to judge them to be at risk of experiencing severe psychological distress as they go through puberty and to have full parental support for the use of pubertal suppression

They also had to be in reasonable shape in terms of endocrine function, body mass index (not significantly underweight) and bone mineral density and have a karyotype consistent their natal sex, so no DSDs or Intersex conditions, although elevated levels of androgens in natal females consistent with polycystic ovarian syndrome were not grounds for exclusion from the study.

Finally they had to be free of any serious psychiatric comorbidities, with the paper listing psychosis, bipolar condition, anorexia nervosa and severe bodydysmorphic disorder unrelated to Gender Disorder as examples. There is no explicit mention of Autism or Autistic Spectrum Disorders in the paper but it’s reasonable to assume that this would be considered grounds for exclusion from this particular study.

In simple terms, the recruitment criteria for this study amounts to cherry-picking from amongst the children and adolescents referred to the Tavistock Clinic the very best candidates for pubertal suppression, those with what amounts to a clear diagnosis of early onset gender dysphoria with few, if any, complications or potential confounding factors. This is not a study designed to assess the validity or otherwise of using puberty blockers within the wider population of children and adolescents referred to the Tavistock Clinic with gender identity issues, it is study designed to validate the use of pubertal suppression in a small and very specific sub-group of that population, one that is by far the least likely to desist from moving on to cross-sex hormones and pursuing full surgical gender reassignment when that option becomes available to them. Indeed, in the case of this specific sub-group of individuals it is arguable – and indeed has been argued forcefully by trans-activists – that pubertal suppression is, itself, an unnecessary step and that these individuals would be better served by moving more or less immediately on to cross-sex hormones, if that is indeed possible. I say that only insofar as, not being an endocrinologist, I’m uncertain as to whether or not the use of GnRHa is clinically necessary, at least for a short period, as a precursor to taking cross-sex hormones

Indeed one of the counter-arguments put forward by trans-activists in the wake of Bell v Tavistock in respect of the evidence relating to the very high proportion of young people in both the Dutch and Tavistock studies who do move on from pubertal suppression to cross-sex hormones and beyond is that this merely demonstrates good diagnostic practice on the part of the clinicians involved in the trials, a view that I’m not entirely unsympathetic towards.

However, as this passage of testimony from a 2015 House of Commons Select Committee Inquiry into Transgender Equality shows, it’s not quite that simple:

We are surprised because we would have expected, in light of the comments we have been hearing about the views in society, that young people are more able to speak out at an earlier point if they feel that their gender identity is an issue at an earlier point. We could take this in a number of ways. One is to ask whether we are doing enough to make sure that younger children, if they need to come forward for support and early intervention, know enough so that the people who are advising them know enough about it. There is also the issue that a large proportion of our young people are not clear that they want help and support until they are in or coming out of puberty. This is the surprise to us: that many of the young people, and increasing numbers of them, have had a gender‑uncontentious childhood, if you like, and it is only when they come into puberty and post‑puberty that they begin to question. That now represents a substantial proportion of our group. A lot of the Dutch published research is in lifelong or longstanding gender dysphoria. They are the ones who have been followed through across four time points in the latest research that sees them as having done incredibly well. These are young people who have been identified early or have identified themselves early and have had the benefit of physical intervention, if that is what they wanted.

The important thing to say—and this question is a platform for saying it—to really support what Jay [Dr Jay Stewart, Gendered Intelligence] is saying, is the heterogeneity of the group of young people coming forward for referral. As you know, our numbers have doubled every year for the last five years and the range and the sort of presentation we are seeing is varying so much. We are not having what you might see as the ones who are in the highly regarded Dutch study, which is this group of now 55 young people being tracked over time, who have had lifelong GIDS, very supportive families and very few associated difficulties. That sort of profile is a very small proportion of our young people. The range, the terms of gender binary—we are having more and more young people coming forward with really quite disrupted attachment histories; more looked-after children. On a typical referral day, we are really concerned about the complexity of many of the young people coming forward. My point about that is that many of them are not identifying their gender issues as being deeply significant to them until their mid‑teens. [Emphasis added]

Oral testimony of Dr Bernadette Wren to the Women’s Equality Committee inquiry into Transgender Equality, 15 September 2015.

This is particularly true of natal females.

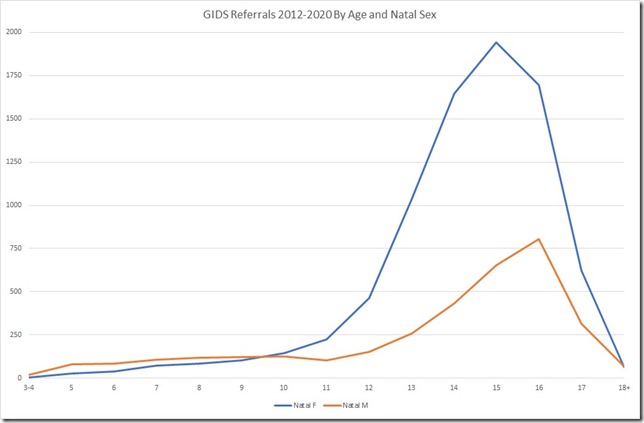

From searching through various sources, including data released via FOIA requests, I pulled together a set of figures for referrals to GIDS between April 2012 and March 2020 broken down by age and natal sex. Out of 13,066 total referrals, I have aggregated data by age and natal sex for 11,631 referrals (89%). The missing data is accounted for, in part, by referrals for which the natal sex of the individual was not known at the point of recording but also by, in some cases, sizeable chunks of data being missing. The worst example of this is 2014-15 where out of 1,316 total referrals just 676 were coded by age and natal sex in the data released via FOIA.

So it’s not perfect but there’s enough data to make some reasonably reliable observations about referrals to GIDS, the key one being the marked divergence in trends between natal males and natal females that kicks in around 10-11 years of age.

So what we’re looking at here is the cumulative referral data for 2012-2020 and we can see that, broadly speaking, the trend in referrals for natal males and natal females is quite similar up until the age of 10 before diverging markedly, and indeed spectacularly so once we get to the early teens. Up until the age of ten there are roughly 3 natal males referred to GIDS for every 2 natal females. From 11-17, that ratio becomes 3 natal females for every natal male. That’s a pretty dramatic shift and one that merits further detailed investigation.

So far as identifying trends in terms of Early Onset Gender Dysphoria, that’s tricky because we don’t have data beyond the age at referral to GIDS, there’s no audited data in the public domain to indicate how long individuals might have been being seen by their GP or local mental heath services in regards to gender-related issues prior to referral. All we can say is that referrals for individuals under the age of 11 are those most likely to relate to Early Onset GD and these account for just 9% of all referrals of natal females but 27% of referrals of natal males. Beyond that we have only the view put forward by Dr Bernadette Wren in 2015 that “many of the young people, and increasing numbers of them, have had a gender‑uncontentious childhood, if you like, and it is only when they come into puberty and post‑puberty that they begin to question”.

The point here is that even if we accept the trans-activists’ view that the evidence put to the court in relation to adolescent progression from puberty blockers to cross-sex hormones amounts to no more than evidence of accurate diagnosis on the part of clinicians at the Tavistock that view is applicable only to a small proportion of the total number of individuals referred to GIDS, particularly when it comes to natal females.

What we have here is a problem described by Ben Goldacre in his excellent book ‘Bad Pharma’:

As we have seen, patients in trials are often nothing like real patients seen by doctors in everyday clinical practice. Because these ‘ideal’ patients are more likely to get better, they exaggerate the benefits of drugs, and help expensive new medicines appear to be more cost effective than they really are.

In the real world, patients are often complicated: they might have many different medical problems, or take lots of different medicines, which all interfere with each other in unpredictable ways; they might drink more alcohol in a week than is ideal; or have some mild kidney impairment. That’s what real patients are like. But most of the trials we rely on to make real-world decisions study drugs in unrepresentative, freakishly ideal patients, who are often young, with perfect single diagnoses, fewer other health problems, and so on.

Are the results of trials in these atypical participants really applicable to everyday patients? We know, after all, that different groups of patients respond to drugs in different ways. Trials in an ideal population might exaggerate the benefits of a treatment, for example, or find benefits where there are none. Sometimes, if we’re very unlucky, the balance between risk and benefit can even switch over completely, when we move between different populations.

And we have the same problem here. By cherry-picking the best possible candidates the Tavistock Study, and the Dutch study on which its based runs the risk of exaggerating both the benefits of pubertal suppression and the persistence rate amongst those to whom it’s prescribed. That last point is one has literally come back to bite the Tavistock Clinic on the arse because by focussing its research efforts on their ideal candidates for pubertal suppression it has fatally undermined, at least in the eyes of the High Court, a central plank of its own stated position on the purpose of pubertal suppression, namely that their primary purpose “is to give the young person time to think about their gender identity”*.

*As per Bell v Tavistock, paragraph 52

Despite the obvious limitations of the Tavistock Study relative to their patient population, preliminary results from the study were used as justification to expand the parameters of the clinic’s use of pubertal suppression both in terms of assessing baseline eligibility to commence treatment based on pubertal development rather than age, hence the High Court being provided with statistical evidence showing that in 2019/20 there were three referrals from GIDS for pubertal suppression of individuals aged either 10 or 11 years of age, and an expansion of the use of puberty blockers beyond the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the study, as evidenced by written evidence submitted to the 2015 Transgender Equality inquiry by Dr Polly Carmichael:

We offer assessment and treatment not just to those young people who are identifiably resilient and for whom there is an evidence base for a likely ‘successful’ outcome. We have carefully extended our programme to offer physical intervention to those who have a range of psychosocial and psychiatric difficulties, including young people with autism and learning disabilities, and young people who are looked after. We have felt that these young people have a right to be considered for these potentially life-enhancing treatments. This has involved careful liaison with local service mental health providers and Social Care, who may know these young people well and who have particular responsibilities for their well-being. Indeed, the service has no record of refusing anyone who continues to ask for physical intervention after the assessment period. Some young people back off from physical treatment at an early stage, but the majority who choose to undertake physical interventions stay on the programme and continue through to adult gender services where surgery becomes an option.

What are we to make of the statement that “the service has no record of refusing anyone who continues to ask for physical intervention after the assessment period”? What, even if they were assessed as being unsuitable by the clinic’s own standards and guidelines?

There’s a caveat because we are told that some young people back off from physical intervention at an early stage but not why? Is this because they’ve reconsidered and decided that gender reassignment isn’t for them after all. Is it because they experienced side effects from the treatment which they were unwilling or unable to tolerate?

And which interventions is Carmichael referring to here? Just puberty blockers, or is she referring also to patients who move on to cross-sex hormones?

The are all questions that remain unanswered at the present time.

Coming more or less full circle, WPATH’s stated position that two specific clinical objectives justify intervention with puberty suppressing hormones:

(i) their use gives adolescents more time to explore their gender nonconformity and other developmental issues; and (ii) their use may facilitate transition by preventing the development of sex characteristics that are difficult or impossible to reverse if adolescents continue on to pursue sex reassignment.

The more I read, the more I am coming to suspect that the first of those justifications is a lie, one that many clinicians tell themselves in order to frame the use of pubertal suppression in terms its benefits to their patients’ well-being rather than their own.

There is a fascinating paper on clinicians’ views and experiences by Vrouenraets et al. “Early medical treatment of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria: an empirical ethical study” (2015) which notes the marked uncertainties expressed by clinicians involved in the treatment of adolescent Gender Dysphoria in relation to pubertal suppression.

The interviews and questionnaires show that the discussion regarding the use of puberty suppression goes in diverse directions and is in full swing. It touches on fundamental ethical concepts in paediatrics; concepts such as best interests, autonomy,and the role of the social context. It is striking that the standards of care for GD of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and the Endocrine Society are considered too liberal and too conservative. Furthermore, since the start of this study, puberty suppression has been adopted as part of the treatment protocol by increasing numbers of originally reluctant treatment teams. More and more treatment teams embrace the Dutch protocol but with a feeling of unease. The professionals recognize the distress of gender dysphoric youth and feel the urge to treat them. At the same time, most of these professionals also have doubts because of the lack of long-term physical and psychological outcomes. Most informants acknowledge pro-arguments and counterarguments regarding the use of puberty suppression. Several teams, who work according to the Dutch protocol, are also exploring the possibility of lowering the current age limits for early medical treatment although they acknowledge the lack of long-term data.

There are at least some ostensibly responsible clinicians who take the view that they are sufficiently confident in their diagnoses that believe the use of pubertal suppression could be safely dispensed with, allowing their patients to move more or less immediately on to cross-sex hormone and in some cases, perhaps even surgery. Others clearly aren’t so sure, in which the case the obvious benefit of pubertal suppression, which WPATH classifies as a being ‘fully reversible’, is that it makes it easier to punt decisions on the use of partially reversible treatments i.e. cross sex hormones, or irreversible ones (most relevant surgeries). safely down the road to a point in time where legal and ethical questions about their patients’ competence to give informed consent become a moot point.

It’s noticeable, for example, that the Endocrine Society’s Clinical Practice Guidelines offer this ‘evidence’ in support of its recommendation that use of cross-sex hormones should begin at 16 years of age.

In many countries, 16-yr-olds are legal adults with regard to medical decision making. This is probably because, at this age, most adolescents are able to make complex cognitive decisions. Although parental consent may not be required, obtaining it is preferred because the support of parents should improve the outcome during this complex phase of the adolescent’s life.

That’s not evidence or even an argument based on any kind of clinical evidence. That’s a legal argument. In many countries, including the UK, 16 year olds are considered in law as being capable of giving independent consent to medical treatment. Kicking these legally and ethically complex decisions down the road until patients reach that age means in many cases there will be no complicated questions of competence and consent to deal with and nothing, therefore, that’s likely to come back and bite clinicians on the arse if anything goes wrong and they get sued for malpractice further down the line. The actual effects of pubertal suppression are largely incidental to that line of reasoning. As long as it’s not shown to be positively harmful then it’s a viable means of managing patients until they’re legally considered old enough to decide whether to take up courses of treatment where the effects are only partially reversible should they change their minds at a later date, obviating the clinician of any potential responsibility or liability should that decision prove to be mistaken.

Before finishing I want to rewind back to the written statement of Dr Polly Carmichael from 2015 and her assertion that “the service has no record of refusing anyone who continues to ask for physical intervention after the assessment period” in the context of evidence revealed during Keira Bell’s judicial review and published at paragraph 29 of the full judgment.

As it is, for the year 2019/2020, 161 children were referred by GIDS for puberty blockers (a further 10 were referred for other reasons). Of those 161, the age profile is as follows:

3 were 10 or 11 years old at the time of referral;

13 were 12 years old;

10 were 13 years old;

24 were 14 years old;

45 were 15 years old;

51 were 16 years old;

15 were 17 or 18 years old.

For the year 2019/20, therefore, 26 of the 161 children referred were 13 or younger; and 95 of the 161 (well over 50%) were under the age of 16.

From which it also follows that 66 individuals aged 16 or over were referred by GIDS for puberty blockers, amounting to just under 41% of all referral even though, at 16 years of age those individuals were at least notionally capable of moving straight onto cross-sex hormones? After all, of the 43 individuals enrolled in the Tavistock Study who did move on to cross-sex hormones the latest to do so, in terms of their chronological age, started cross-sex hormones at 16.5 years of age.

At yet we still have patients at GIDS being referred for puberty blockers at 16, 17 and even 18 years of age?

Can we assume that most of these individuals are the ones with “really quite disrupted attachment histories” and the ones with“a range of psychosocial and psychiatric difficulties” including autism and learning disabilities. There may even be some who are “not identifying their gender issues as being deeply significant to them until their mid‑teens” and who may even have “had a gender‑uncontentious childhood”? The difficult, potentially risky cases? The ones that don’t fit neatly within the carefully constructed inclusion/exclusion criteria of the very limited range of studies on which the Tavistock Clinic has relied upon to validate its clinical practices and, latterly, as evidence in court when the legality of those practices was made subject to judicial review?

One can argue, of course, that these are precisely the kind of people who need to be given “more time to explore their gender nonconformity and other developmental issues”. Equally, these are also the riskier candidates for gender reassignment, the ones where, from the clinicians perspective, you really don’t want any lingering legal and ethical question marks about their capacity and competence to give informed consent to treatment if things go sour further down the line. The one’s where its much safer for the clinician to punt any decisions on treatments that are not judged to be fully reversible far enough down the track to limit their legal liabilities.