[This is the first of two articles looking in depth at testimony given to a Pennsylvania District Court by Gail Dines while acting as an “expert” witness for the US Department of Justice and, as you might well imagine, it’s a pretty long article so for the sake of convenience, if you’d prefer to read it offline using an e-book reader then you can download it as a PDF. Part one, which is that part, deals with Dines’ attempt to analyse porn-related search engine traffic. Part two, which will be posted in a few days, deals with her analysis of the content of porn tube websites and will include not only an overview of how and why the porn industry boomed in the late 1990’s but also more original research which produced results some may find a little surprising.]

Now here’s an interesting situation…

In my last monster article on Gail Dines’ use of extremely dubious and woefully outdated Internet porn ‘statistics’ on the ‘facts and figures’ page of her Stop Porn Culture website there is one section which looks at a couple of claims about the prevalence and popularity of ‘teen porn’ which Dines claims as her own original work, giving a reference to an article published on the Counterpunch website at the beginning of August 2013.

These are Dines’ claims as they appear on her Stop Porn Culture site:

Globally, teen is the most searched term. A Google Trends analysis indicates that searches for “Teen Porn” have more than tripled between 2005-2013, and teen porn was the fastest-growing genre over this period. Total searches for teen-related porn reached an estimated 500,000 daily in March 2013, far larger than other genres, representing approximately one-third of total daily searches for pornographic web sites. (Dines, 2013)

And here’s how those claims were presented in the Counterpunch article:

Following the Ashcroft decision, Internet porn sites featuring young (and very young-looking females) exploded, and the industry realized that it had hit upon a very lucrative market segment. Our research demonstrates that “teen porn” has grown rapidly and is now the largest single genre, whether measured in terms of search term frequency or proportion of web sites. A Google Trends analysis indicates that searches for “Teen Porn” have more than tripled between 2005-2013, and teen porn was the fastest-growing genre over this period. Total searches for teen-related porn reached an estimated 500,000 daily in March 2013, far larger than other genres, representing approximately one-third of total daily searches for pornographic web sites. We also analyzed the content of the three most popular “porntubes,” the portals that serve as gateways to online porn, and found that they contained about 18 million teen-related pages – again, the largest single genre and about one-third of the total content.

This last article was written in the wake of Dines making an appearance in court, in June 2013, as an ‘expert’ witness for the US Department of Justice (USDOJ) in a long, drawn out and extremely complex court case (Free Speech Coalition v. Holder) in which the Free Speech Coalition (FSC), a trade body representing the US adult entertainment industry, and others are challenging the legality and constitutionality of the 18 U.S.C. § 2257 regulations, which require anyone in the US producing sexually explicit visual media to maintain detailed records of any persons depicted in that media. This is, ostensibly, intended to ensure that no one under the age of eighteen, the minimum age at which someone is permitted to appear in a pornographic video/image as a performer/model in the US, is used the making of pornography and the regulations impose criminal penalties for non-compliance of up to five years imprisonment. The case itself is extremely complex, as often tends to be the case in the US First Amendment cases, and is unfortunately open to wilful misinterpretation and misrepresentation, a feature which Dines cheerfully exploits in her Counterpunch article, but if you are interested in the detail then there is an extremely comprehensive set of information and resource materials to be found at the ‘XXXLAW’ website, which is run by the law firm JD Obenberger and Associates. Although not, strictly speaking, NSFW I would suggest you not try to access this site from the office given the nature of the issues it deals with.

So far as a tl;dr version of all that goes the main thrust of the Free Speech Coalition’s case is that the 2257 regulations, as they currently stand, are overbroad in scope and extend to a wide range of audio visual materials that are not specifically pornographic and that the record keeping and spot inspections regime created by the regulations far exceeds what is necessary or reasonable to achieve their stated purpose. I’m not about to try and judge the merits of those arguments but it is fair to say that in more than 30 years there have been no more than two or three documented cases of underage performers appearing in legal pornographic magazines and films/video – including that of Traci Lords, which to a considerable extent led to introduction of the 2257 regulations – and in all those cases the performers managed to obtain work in the industry by using false ID which gave the appearance that they were older than they actually were.

As for the ‘Ashcroft decision’ Dines mentions in her Counterpunch article, that was a completely separate case, Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition 535 US 234 (2002), dealing with the scope of legal provisions relating ostensibly to child pornography, which were introduced in 1996, which the US Supreme Court struck down in 2002 after finding that the law, as written, was overbroad and would “speech despite its serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” – examples of the kind of material that could have been caught up in this law that were cited during the case including Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film version of Romeo and Juliet and Sam Mendes’ Oscar winning “American Beauty”.

As part of the research for my previous article on Dines’ use of statistics I attempted replicate the analysis that Dines purported to have carried out in order to arrive at the various claims she made in the Counterpunch article, using the limited amount of information contained within it, and discovered that in all but one case – the 500,000 figure cited as an estimate of the number of daily searches for ‘teen porn’ – I was unable to satisfactorily reproduce any of her claimed figures or estimates.

So, I published what I’d found and then, having spotted one or two curious trends in the figures I’d been working with that merited further investigation and also after noticing that one of the porn tube sites I’d been extracting data from (Pornhub) was busily updating its front end interface and making more of its content accessible, I decided to continue working on the questions posed by Dines’ botched analysis while, at the same time, casting around for additional information which might help to explain how she’d arrived at the figures she’d used in the Counterpunch article – and it was while I was doing this I ran across a copy of the judge’s ruling and opinion in FSC v. Holder from which it quickly became apparent that what Dines was actually citing in her article were figures and statistics she had produced in court as part of her ‘expert’ testimony for the USDOJ.

Now that rather ups the ante because it’s also apparent from Judge Baylor’s ruling in the case, which will undoubtedly be winging its way back too an appellate court in due course, that although he chose to dismiss much of Dines’ testimony on the grounds of obvious personal bias he did place a considerable amount of store in the statistical information she gave to the court:

The government offered testimony from four expert witnesses, each of whom covered a different topic. Dr. Gail Dines, a professor at Wheelock College, testified about the quantity of commercial pornography on the internet that shows youthful-looking performers. Dr. Dines is a sociologist with extensive experience in studying and writing about pornography on the internet. She related that of the 61 genres of pornography available on “pornhub,” a popular tube site4 for commercial pornography, the “overriding image is of a youthful-looking woman.” (Audio File 6/7/13 A.M. at 0:41-0:43) (ECF 203). This image pervades even those genres that purport to focus on older looking women, such as “MILF” porn. (Id. at 0:43, 0:54-0:56).5 Additionally, Dr. Dines testified that the largest genre of pornography on tube sites is “teen porn,” accounting for approximately one-third of those sites’ material. (Id. at 1:07-1:09). Images in the teen porn genre tend to show models with little to no body hair, slim figures, and props such as teddy bears, pigtails, and pom-poms, to suggest youthfulness and even childhood. (Id. at 0:45-0:48). Dr. Dines testified that teen porn is not only the largest genre of pornography on the internet in terms of total quantity, but also one of the most sought-after genres of pornography. SEObook, a website which reports the frequency of searches for specific terms or keywords, shows there are approximately 500,000 searches a day for “teen porn” and similar entries, compared to 1 million searches a day for the term “porn.” (Id. at 0:57-1:00). Google trends, a website which also provides information on search term frequency, indicates searches for “teen porn” have grown 215% between 2004 and 2013. (Id.).

There are also two explanatory footnotes attached to this section of the ruling, which appears on pp. 17-18:

4 From the testimony at trial, it appears that “tube sites” are adult content websites that host a broad range of sexually explicit depictions, including professionally made videos and user-generated videos that are uploaded by subscribers to the site. Tube sites function as “portals” to much of the pornography on the internet because they are accessible by anyone and they offer a considerable amount of content for free. As individuals click through the free content, they will eventually arrive at entry-ways to paid-pornography websites, which they can only access by paying to become a subscriber or member. (Audio File 6/7/13 A.M. at 0:27-0:29).

5“MILF” is an acronym that stands for “mother I’d like to f*ck.” Dr. Dines found that the two most popular types of videos in the “MILF” genre on pornhub are videos in which a woman is seducing a young girl to deliver her to a man, and videos in which an older woman is engaging in sexual activity with a younger girl or boy. Both types of videos thus contain not only mature-looking adults, but also youthful-looking performers. (Audio File 6/7/13 A.M. at 0:55).

On pp. 33 of the ruling Judge Baylor offers his opinion of Dines’ evidence as follows:

First, the statistical data of Dr. Dines was more methodologically rigorous than that presented by any of Plaintiffs’ experts. As explained above, it showed that “teen porn” accounts for approximately one-third of the material on pornography tube sites, that it is one of the most frequently – if not the most frequently sought – genres of pornography, and that it has grown by over 200% between 2004 and 2013.

From which we can reasonably conclude that in the court of the blind, the one-eyed anti-porn activist is king, especially when the trial judge is no more clued in on how the Internet works than Dines and when the FSC’s own expert dropped the ball by taking entirely the wrong approach to his own analysis.

Okay, so what I’ve done is work through the judge’s ruling and this report of Dines’ testimony published by Adult Video News during the hearing, which provides a little more detail both on what Dines said to the court and, at a couple of points, how she obtained some of her ‘statistics’ and then carried out my own detailed analysis of the main points of her evidence. It does have to be said at this point that Dines informed the court that is was the USDOJ that approached her to act as a witness and that they asked her to carry out a qualitative analysis of the content on a number of adult entertainment websites when, by her own admission, Dines is a ‘qualitative sociologist’ with no particular background, experience or expertise in qualitative analysis.

Dines also testified that the Justice Department (DOJ) had asked her to map the content on the various internet adult sites, starting with the free ones, the creation of which she described as a “revolution in the porn industry,” and to collect data on the prevalence of the word “teen” in those sites’ offerings. [AVN Report]

So it’s not just her judgement and status as an ‘expert’ that’s being questioned here but also the judgement of the US Department of Justice.

DINES’ EVIDENCE – SEARCH ENGINE TRAFFIC

Before getting into the detail I should provide an overview of the various data sources and methods used to produce my own analysis, so:

Estimates for the size and growth of the global Internet population since 2004 – i.e. the numbers of people with access to the Internet – were obtained from the Internet World Statistics website and cross referenced with data from the International Telecommunications Union.

Estimates for the growth in Google’s overall daily search traffic since 2004 are based on data obtained from Google and Comscore Media Matrix and were cross-referenced with data from several other Internet metrics companies to check their reliability.

Data on keyword searches and search trends was obtained via Google Trends.

For this analysis, weekly search trend data from January 2004 to March 2014 was extracted using individual keyword searches for ‘porn’ – this is, unsurprisingly, the commonly used keyword used by people searching Google for pornography – and for thirty porn subgenres/niches including niches defined by the apparent age of performers; their ethnicity and nationality, sexual orientation/gender identity, and a set of fourteen niches defined in terms of specific sex acts or other characteristics with the aim of reflecting both common and minority niche interests amongst porn consumers.

All keywords were selected from taxonomic categories and tags commonly used on pornographic sites and were combined with the keyword “porn” to ensure that the data obtained from Google Trends reflected only searches for pornography and each keyword was checked against several variants, including keywords using alternative generic terms for “porn” such as “XXX”, to ensure that it was the most commonly used keyword for a particular niche and in all but one case a single phrase in the form “[keyword] porn” was found to be the most common search term used in each niche. The sole exception to this was the ‘alternative’ niche in which features performers who are often heavily tattooed and/or have several piecing many of whom are depicted as Punks or Goths, where the term ‘Emo’ has emerged since 2008 to become the most commonly used search term for this niche. To capture the full trend for this back to 2004, the trend data for the keywords “Punk”, “Goth”, “Tattoo” and “Emo” was combined by taking the highest for any individual keyword for each week in the four data sets.

This generated a total of thirty one data sets, including the data set for all searches including the keyword “porn” in which the weekly trend in each niche data set is subset of the main “porn” trend.

All trend data provided by Google Trends is supplied in the form of normalised relative trend scores out of a maximum value of 100 rather than providing absolute figures for the actual quantity of search traffic but the Trends website does permit comparison of up to five different keywords on a single trends graph with the individual trends for each keyword shown relative to the others four. Using this feature, I then ran a series of overlapping trend comparisons for all thirty-one keywords from which the monthly trend score for March 2014 was used to generate a scaling factor for each keyword, allowing all thirty-one data sets to be combined into a single data set containing scaled weekly trend data for each keyword relative to all the others. The scaled trend data was then normalised using the adjusted weekly trend scores for main “porn” trend to generate a combined data set showing the number of searches for each niche keyword per week per 100,000 searches including the word “porn” and the weekly data combined to give an average monthly figure for each month from January 2004 to March 2014.

Additional data on overall traffic levels and the amount of traffic generated by Google searches for the nineteen most popular – i.e. highest traffic – porn tube websites in March 2014 was obtained from the Internet metrics company Similarweb and this was combined with data from Google Trends, using the combined data for the most popular porn tube (XVideos) as a reference point, to generate estimates for the average number of Google searches for “porn” and for each niche keyword per day during that month.

That covers the main work done on porn-related search engine traffic but for a few additional pieces of data obtained, from Google Trends, looking at regional search trends for specific niches – i.e. where in the world the largest numbers of searches for certain type of porn are coming from – and at the most popular niche porn search terms in individual US States, which directly addresses a point made by Dines in her evidence to the court.

So, moving on to Dines’ evidence, this is what she had to say in relation to her investigations of general search traffic to porn tubes:

Google trends, a website which also provides information on search term frequency, indicates searches for “teen porn” have grown 215% between 2004 and 2013. [FSC v Holder ruling]

SEObook, a website which reports the frequency of searches for specific terms or keywords, shows there are approximately 500,000 searches a day for “teen porn” and similar entries, compared to 1 million searches a day for the term “porn.” [AVN Report]

Statistics found on PornMD.com said that the most searched terms are “MILF,” “teen” and “college”—half a million such searches per day, and far and away more searches than other porn-related terms like “anal,” “Asian” or “gay.” [AVN Report]

PornMD had found that in 13 states, “teen” was the most searched porn term. [AVN Report]

Before we get into any figures there are a couple of very basic errors of fact to correct in the last two statements, assuming these have been reported accurately by AVN.

PornMD.com is nothing more than a search engine owned by the Luxembourg-based multi-national corporation Mindgeek (formerly Manwin until October 2013) which owns and operates what is currently the largest network of porn tubes and other adult sites, which includes four of the top ten most visited adult websites (Pornhub, Redtube, Youporn and Tube8) and a number of content brands and associated pay sites (Brazzers, Digital Playground, Mofos) in addition to managing websites and other services for Wicked Pictures and, in Europe, for Playboy. PornMD.com does nothing more than enable its users to search for porn videos hosted on Mindgeek’s main network of nine porn tubes (the four already noted plus XTube, Spankwire, Keezmovies, ExtremeTube and Mofosex) with search results displayed via a porn tube style interface with some options to filter the results by site, date added and video length. What PornMD doesn’t provide – at all – are any search statistics other than a head count of the number of videos on the Mindgeek network that match whatever search term a user has entered so it would appear that in that part of evidence to the court that Dines has confused PornMD.com with Google Trends, from which that kind of traffic data can be obtained, unless AVN has made an error in reporting her testimony to the court.

With those errors noted, let’s look at the first substantive claim in this section, which is that the number of searches for “teen porn” grew by 215% between 2004 and 2013, although her Counterpunch article refers to such searches having “more than tripled between 2005-2013”. The actual figure is 216.38%, based on comparison of the relative figures from Google Trends for January 2005 and May 2013, which is when Dines did her analysis, although if you go back to the earliest data Google Trends provides (January 2004) the percentage increase rises to 307.78%.

Superficially, therefore, it might appears that Dines is correct in her assertion to the court but what she ignores is that she not dealing with search traffic generated by a static population of Internet users over a period of time. The total number of searches for “teen porn”, and for porn generally, may have grown over that eight year period but so too did the number of people with access to the Internet. In January 2005, it’s estimated that a little under 841 million people worldwide had access to the Internet. By May 2013 this had grown to something over 2.64 billion people, an increase of around 214%, which raises the question of whether or not Dines claimed increase in interest in “teen porn” is purely a result of demographic change; i.e. more people online equals more searches for porn and for certain sub genres but not any substantive increase in interest in a particular genre.

This is why I put a lot of time and effort into generating a normalised data set showing the number of searches for individual niches per 100,000 porn searches; because that data set will show whether or not there has genuinely been an increase in interest in a particular niche over time as opposed to just a demographically driven increase in the absolute amount of search traffic containing a particular niche keyword.

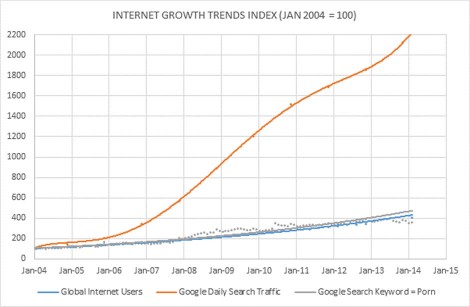

This brings us to our first piece of concrete evidence (fig. 1) which shows the indexed growth trend from January 2004 to March 2014 for three metrics; the global number of people with access to the Internet, Google’s average daily search traffic and the average number of daily Google searches which include the keyword “porn” and the graph very clearly shows that the trends for global Internet population and porn searches run very close to together along a very similar trajectory, while the general search traffic trend is heading off into the stratosphere by comparison. Over the eleven period for which we have data the amount of search traffic looking for porn has grown by an average of 1.1% per year over and above the estimate growth in the number of people with access to the Internet, which on the figures we’re looking at is well within the likely margin of error. By comparison, general search traffic has been growing at around sixteen times that rate, all of which is consistent with the view from my own past research into ‘zombie’ porn statistics that estimates of the prevalence and popularity of online porn dating back to the late 1990s and early 2000s will tend to massively overestimate both the overall amount of pornographic content online and the amount of interest in that content due to the porn industry’s status as an early adopter of Internet technology.

Figure 1. Indexed growth trends for number of Internet users, Google’s daily search traffic and daily search traffic including the keyword ‘porn’ from January 2004 to March 2014.

What this particular graph doesn’t illustrate at all well, however, is the difference in scale between the total amount of search traffic going through Google on a daily basis and the amount of that search traffic which is generated by people looking for porn. Based on the most recent estimates I have, which are for December 2013, Google currently processes around 3.76 billion searches per day of which around 16.4 million searches (0.44%) include the keyword “porn” and this one keyword appear to be used in at least half of all general keyword based searches for pornography. After adding in estimates for the proportion search traffic being generated by direct searches for specific porn websites, using data from Google Trends and SimilarWeb, the figures I have suggest that around 1.5%-2% of all global Internet search traffic is generated by people searching for pornography but to put that in perspective that is still less that the amount of search traffic generated by Wikipedia (2.8%), YouTube (2.45%) or Facebook (2.2%) just on their primary .com domains.

So that’s the general picture, but what about “teen porn” as a specific niche?

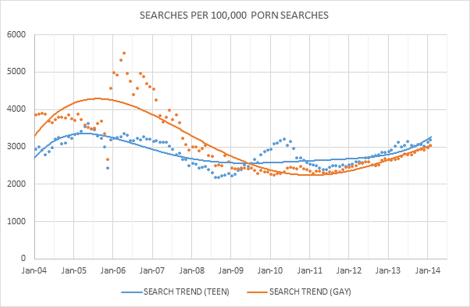

We can begin to a get a general idea by looking at the normalised trends for the two most sought after porn sub genres, in terms of Google search traffic – “gay porn” and “teen porn” – both of which account for roughly 3,000 of every 100,000 searches which include the keyword “porn” (fig. 2) from which it is apparent that the general trend for both keywords over time has remained pretty stable.

Coupled with what we’ve already seen of the general trend in searches for pornography (fig 1.) the trends here again show that broadly speaking any growth in the absolute amount of search traffic for either niche is no more than a product of the overall growth in the number of Internet users over the same period of time. On a purely straight-line trend, which is a not a particular good fit for the actual data but nevertheless useful for purely illustrative purposes, annualised growth in interest in “teen porn” as a distinct sub-genre would amount to just 0.69% per year over the last eleven years with “gay porn” seeing a modest falloff in interest of just under 3% per year.

Figure 2. Search trends for the keywords “gay porn” and “teen porn” in numbers of searches per 100,000 searches including the keyword “porn” from January 2004 to March 2014.

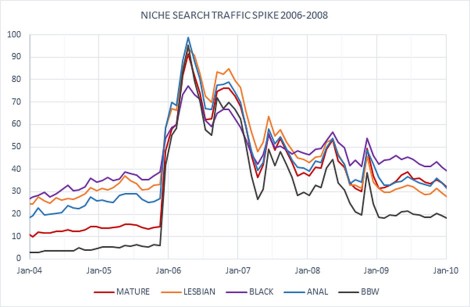

One feature of this graph that is particularly interesting is the sudden spike in search traffic looking specifically for “gay porn” that occurred in the first few months of 2006, after which the overall trend took around 18 months to subside back to a level much closer to the 2004-2006 trend. This traffic spike can be seen most clearly in the raw Google trends data for several niches which all show this same effect (fig.3) – and do note that the graph shows only a subset of the total number of keywords in which this trend is evident.

Figure 3. Sudden spike(s) in search traffic across several niches between 2006 and 2008/9.

Clearly there is something very interesting going on here, but what exactly and what bearing might this have on the evidence that Dines gave in court in regards the presumed popularity of “teen porn”

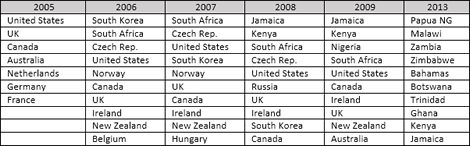

Unfortunately Google Trends limits the scope of its timeframe analysis tool to whole years for search trend data that’s more than 12 months old, so it’s not possible to investigate each sudden traffic spike on the graph for an individual cause. Nevertheless, tables showing the top 10 countries for a specific search term by year are available and these do shed some considerable light on the likely cause(s) of these sudden spikes in traffic as can been seen in the table (fig. 4) which shows the countries that were generating the largest number of searches for “black porn” for each year between 2005 and 2009 and for 2013, the most recent year for which a full year’s data is available.

Figure 4. Countries generating the most searches for “black porn” by year, 2005-2009 & 2013

What this is telling us is that explanation for the spikes in porn-related search engine traffic and, indeed, much of the general trend in such traffic since 2006 lies in two things; Google’s expansion in to new regional and local markets via localised multi-lingual versions of its main search engine – this being the most likely explanation for South Korea’s sudden appearance at the top of the “black porn” search rankings in 2006 – and the growth of Internet access outside North America, Western Europe and Australia/New Zealand. For example, figures obtained from the International Telecommunications Union indicate that the number of people in the Czech Republic using the Internet increased from just over 35% in 2005 to almost 52% in 2007, at which the point the country emerged as one of the top three or four sources of search traffic across several porn sub-genres, including black porn (as fig. 4 indicates), anal porn and all the non-heterosexual niches (gay, lesbian and trans).

As more people either gain access to the Internet or, in some cases, access to tools like Google’s search engine which open up a far larger segment of the Internet that might previously have been available, those with a pre-existing interest in pornography will inevitably use the new tools at their disposal to look for material that satisfies their personal tastes, particularly where those tastes were not that well catered for in the local pre-Internet market. For example, the rise of the Czech Republic as significant source of porn-related search traffic between 2006 and 2008 is strongly associated with a substantial rise in searches for Russian pornography, which would have previously been fairly difficult to come by without access to the Internet, but not with any significant rise in people looking for German pornography, which you would expect to have been readily available in the Czech market due to the proximity of the two countries.

In the case of South Korea, where porn is illegal and possession of pornographic material carries a maximum two year sentence, Google’s expansion into that market would appear, at least to begin with, to have offered South Korean porn consumers access to a search engine that was far less restrictive in terms of the kind of content it offered access to than the two main local search engines, Naver and Daum. Internet use in South Korea is subject to overt censorship by a government agency, the Korean Internet Safety Committee (KISCOM) which regularly issues orders to local ISPs requiring them to block access to web sites which are to contain anything from “subversive communications” and “cyber defamation” (i.e. criticism of politicians and government officials) to the old favourite “obscenity and pornography” while search engine providers have been required to implement age verification, using a South Korean national identity number or a passport in the case of foreign nationals in order to use keywords that have been deemed to be “inappropriate for minors”, a system which will, of course, act to restrict the behaviour of adults because it requires them to disclose their identity should they to use any of those keywords. On the face of it, therefore, it seems highly likely that South Korea sudden appearance in Google “smut rankings” in 2006, at a time when it accounted for only 1.9% of the South Korea search market in 2007 is likely to be due to it either not having implemented that age verification system at the time or because savvier South Korean Internet users were able to find a way to bypass that system using Google.

A third factor, which plays a crucial role in the disappearance of North America, Western Europe and Australia/New Zealand from the list of largest sources of porn-related search traffic in many niches, is the emergence since late 2006 of the large porn tube sites offering free access to a large number of porn videos across a wide range of niches, one which provides a key insight into the general behaviour of porn consumers.

Most of the large porn tube sites do not rely heavily on search engine traffic for their regular custom. Based on data obtained from SimilarWeb a little under than 25% of the traffic arriving at the top nineteen porn tubes arrives by way of search engines and for some sites this figure can be as low 3%-5%. The largest source of traffic to these sites (average 47%) is referrals from other porn sites, particularly from what might reasonable be called “meta-tubes”, sites which index and aggregate content from other porn tubes without hosting any content themselves. Currently three of the nineteen most popular conventional porn tubes (DrTuber, Nuvid & SunPorno) derive 85%-90% of their traffic via this route.

What this tells us that the majority of porn consumers will use Google and other generic search engines only for as long as it takes them to find one or two regular and reliable sources of their preferred brand of smut, at which point they’ll cease to rely on the likes of Google, Yahoo and Bing and, instead, go direct to. That explains both the disappearance of countries like the US and UK from Google’s regional search rankings across a large number of relatively common porn sub-genres and why developing countries with growing but still relatively small online populations, compared in particular to the US, are now amongst the largest sources of porn-related search traffic according to Google Trends.

Within this overall trend there are a number of distinct regional variations in terms of interest in specific niches. Just as African countries account for most of the top ten sources of searches for Black porn so countries in South-East Asia are now the largest source of search traffic looking for Asian, Japanese and Thai porn with the rapidly growing market for Indian porn being dominated by Indian, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Fiji, which has a large South Asian population and searches for Russian porn coming mainly from Georgia (the country not the US State), Azerbaijan, Armenia and Estonia. If nothing else, one of the clearest of all trends in porn-related Google search traffic in recent years is “local porn for local people” but it also clear that some niches do not travel as well as others; but for South Africa, both interracial and homemade porn have, so far, remained a particularly Western predilection while interest in BDSM has migrated away from the US only as far as Central Europe with the emergence of Germany, the Czech Republic and Austria as three of five main search markets. Meanwhile, down in the Balkans they appear to go for older women in a big way with Serbia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Croatia taking four of the top five slots in Google’s 2013 rankings for both the MILF and Mature niches.

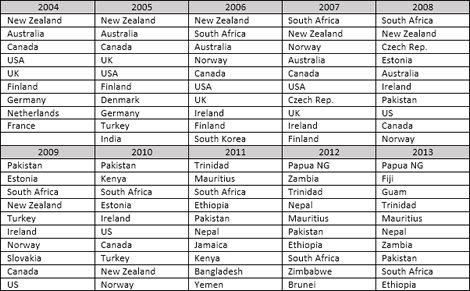

And as for “teen porn”, fig.5 shows the complete top ten countries list from Google Trend for every year from 2004 to 2013 and although the overall trend for this niche does not display the same pattern of sudden traffic spikes as many other niches, the general pattern of a shift in the major sources of search traffic away from North America and Western Europe to other part of the world is clearly evident.

Figure 5. Top countries searching for “teen porn” by year, 2004-2013.

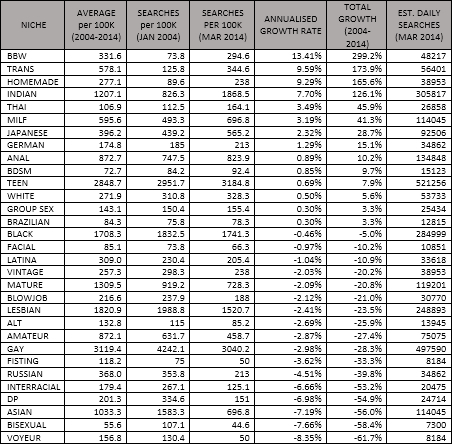

Pulling all the search traffic data from Google Trends and SimilarWeb the following table (fig 6.) provides descriptive statistics for the thirty porn sub-genres and niches including in my own analysis, sorted by the straight line growth in the number of searches as a proportion of all searches in which “porn” appears as a keyword and it is clearly evident from that table that the greatest degree of actual growth in search traffic is seen in small speciality niches; e.g. BBW (Big Beautiful Women), Trans, homemade porn and, to a lesser extent, BDSM and in porn catering to specific ethnic and national identities while niches that are perhaps less appealing to non-Western audiences have seen only marginal growth or a modest decline in search traffic.

In regards to the small number of niches that appear to buck this general trend, the slight drop in interest in “black porn” is likely to be due to lower overall levels of Internet access in Africa compared to the other markets with sizeable Black populations, such as the US, where the vast majority of porn consumers are going direct to porn tubes rather than using general search engines. Interest in “Asian porn” has also declined over time, seemingly as a direct consequence of the increase in searches for specific nationalities (Japanese and Thai) as the main source of such searched has shifted away the US and other Western countries to South-East Asia, while it seems likely that “Russian porn” has seen a similar decline in Google’s search traffic only because the Russian language search market continues to be dominated by a local search engine, Yandex.

Likewise, the fall in search traffic looking for ‘mature porn’ seems likely to be a direct consequence of the growing popularity of “MILF” as a search term, even though the two terms are, to some degree, interchangeable.

Figure 6. Descriptive statistics for niche search trends 2004-2014 (sorted by growth rate).

Although the figures for “teen porn” in this table do validate Dines’ estimate of around 500,000 searches per day, this figure actually amounts to just 3% of all Google searches including the word “porn” and not one third of all searches for pornography, for which she gave an of just 1 million searches per day when, in reality, the figures from Google Trends show that that Google handles around 16.3 million searches per day which include the keyword “porn”.

As her source for these estimates, Dines cites SEOBook, a commercial website which provides a range of information about Search Engine Optimisation alongside training materials and a variety of online tools that can be used to identify keywords relevant to different types of website. Some of information and other content on the site is available free of charge, including a fairly basic keyword tool powered by Wordtracker, but most of the detailed information and specialist SEO Tools are behind a subscription paywall with full access to all the site’s resource costing $300 per month.

The keyword tool is very easy to use; type a base keyword or phrase into the search box (e.g. “porn”), push a button and a couple of seconds later the site spits out a list of 100 ‘popular’ search terms including that keyword/phrase, each with a daily traffic estimate, and a download link via which the list can be quickly downloaded into a spreadsheet for further analysis. To check whether this was indeed the tool used by Dines to generate the traffic estimates included in her evidence I ran three searches using the keywords “porn”, “teen porn” and “teen” and downloaded the result of each search into Excel for further analysis. The 100 search terms returned for “porn” did not include either the word “porn” as a single keyword or the phrase “free porn”, which are the two most common “porn” search terms according to Google Trends but the list did include many fairly common phrases such as “lesbian porn” and “free porn movies” and adding the traffic estimates for all 100 search terms together gave a total figure of 927,000, which is close enough 1 million to the basis of Dines’ estimate. The search for “teen porn” generated a total traffic estimate for all 100 phrases of just under 95,500 searches but the search just for “teen” generated a figure for the total amount of traffic of just under 700,000 searches and a large proportion of the phrases included in list were pretty obviously looking for smut, e.g. “anal teen”, “teen orgasm”, “teen porn tube”, etc., so eliminating any phrases in the list that were too vague to be definitely categorised as a search for pornography, such as “teens” and “teen art” would bring the total figure down to somewhere is the region of 500,000 searches.

However, I then began to cross reference the daily traffic estimates given for some of the phrases in the “porn” and “teen” lists with data from Google Trends for the same search terms and quickly discovered that many of the estimates given by SEOBook’s keyword tool were wildly at odds with the figures from Google Trends. For example, according to the SEOBook tool, the phrases “lesbian porn” and “vintage porn” should generate very similar amounts of traffic – the figure given for “lesbian porn” (23,809 daily searches) is just 6% higher than the figure for “vintage porn” (22,456) despite the fact that a comparison of the two phrases in Google Trends currently shows that current ratio of “lesbian porn” searches to “vintage porn” search is a little over 6:1 and that since 2004 that ratio has never only vary rarely fallen below 3:1. Likewise, the figures given in SEOBook’s “teen” list suggest that the phrases “teen models” and “teen nudist” should each generate around half the amount of traffic generated by the keyword “teen” on its own and yet Google Trends shows that compared to “teen”, which gets a relative score of 86, neither of those phrases generates enough traffic to even register on a Google Trend comparison – both currently score precisely zero.

So it’s abundantly clear that Dines generated the figures she used in court using a tool that is wholly unsuited to the purpose for which it was used, a fact which become perfectly apparent if only you bother to scroll down past the search box to the sale pitch further down the same page and read the caveats, which include:

Offers rough suggested daily search volumes by market for Google, Yahoo!, and MSN.*

And…

Since we estimate Google, Yahoo!, and MSN traffic based on Wordtracker’s keyword data, any sampling error is amplified due to the difference in traffic.

* Please note our tool currently assumes Google having ~ 70% of the market, Yahoo! having ~ 20% of the market, and MSN search having ~8% of the market, and is based on rough math that is less precise than Wordtracker’s computational techniques.

The more observant and tech savvy readers might also have noted the references here to MSN, which hasn’t existed as a search engine brand since 2006 when it was replaced by Windows Live Search, which became just Live Search in March 2007 before being replaced by Bing in 2009.

Clearly it’s been a while since the sales pitch on that page was last updated and the same may very well be true of the data provided by the Keyword Tool, which is really there only to try to prompt visitors to the site to click on one of several Wordtracker affiliate links on the same page from which the site’s owner will generate a bit of advertising revenue. Although the page states that it is “powered by Wordtracker” and “driven off the Wordtracker Keyword Suggestion Tool”, Wordtracker’s own promotional version of this same tool, which appears on their homepage and which returns only ten keywords rather than SEOBook’s 100, serves a very different set of data to that offered by SEOBook. The daily traffic estimate given by Wordtracker for “teen” (103,000) is almost double the figure reported by SEOBook (53,000) and where SEOBook suggests that “teen models” and “teen nudist” are the next most popular terms after “teen”, Wordtracker’s promotional tool offer the suggestions “teen mom” and “teen mom 2”, both references to a US reality show that ran from 2009 to 2012. The difference here may be down to nothing more than Wordtracker omitting adult search terms on its own site but it does tend to reinforce the point that Dines used entirely the wrong tool for the job she was trying to do and hit on a fairly accurate figure for “teen porn” search only as a matter of sheer luck rather than by carrying out any kind of methodologically rigorous analysis.

That leaves only the claim that “teen porn” is the most popular search term in 13 US states, which may well have been the case in May 2013 but currently, using data again from Google Trends, that figure has risen to 16 states with 27 states favouring gay porn and seven, plus the District of Colombia, favouring “black porn” over either to the other two. Beyond providing an excuse to include a fairly nice map showing which type of porn is the most popular in each state (fig 7.) All this actually tells us is that the difference in search traffic levels for “gay porn” and “teen porn” is sufficiently marginal in some states for the number one spot to periodically flip from one to other and back again, although the map is still pretty interesting as it shows the US divided in what are roughly three distinct bands with “teen porn” being most popular in the Pacific North-West and Central regions, “gay porn” running across the South West from California and Nevada through to the Texas and Oklahoma before swinging North East up to New England, while “black porn” achieves its greatest level of popularity in the Deep South from Louisiana up to North Carolina and Maryland, following the line of America’s “Black Belt”.

Figure 7. Most common niche porn search keyword by State, March 2014.

In so far as it makes any difference at all, which is not much, there does appear to be the possibility of correlation between population density and a preference for either gay or teen porn, which could indicate that Wisconsin, New Hampshire and Washington (State) may the swing states that have flipped over from gay porn to teen porn since May 2013, although Wisconsin is also a candidate if perhaps a bit of an outside bet, but otherwise what we’ve seen from the global data clearly indicates that the limited amount of porn-related search traffic generated by the US is of limited relevance given that most US porn consumer bypass search engines like Google and go direct to source.

CONCLUSIONS – THE GLOBALISATION OF PORN

This might seem like a hell of a lot of analysis to deal with just four statements made by Dines in her testimony to the court but what it clearly shows, in the first instance, is that the limited amount of research she put in behind that statement was anything but rigorous, hence the glaring errors and, in particular, her failure to realise that she had woefully underestimated the actual amount of porn-related traffic going through Google on a daily basis, which includes not only 16.3 million searches including the keyword “porn” but also a very similar number of searches (15.6 million per day) which include the name of any one of the five most popular porn tubes (XVideos, XHamster, Pornhub, Redtube & Youporn).

As regards the specific claims made about “teen porn” it is worth noting that in their 2011 book “A Billion Wicked Thoughts: What the World’s Largest Experiment Reveals about Human Desire”, neuroscientists Ogi Ogas and Sai Gaddam analysed the keyword data from 400 million searches conducted using the Dogpile search engine between July 2009 and July 2010 and found that around 55 million of these searches (13%) were looking for some sort of erotic content. Of these searches, 13.5% included youth-related keywords in which the most commonly used adjective was “teen” and this one keyword was found in 5.6% of all sexual searches in the data set and was, therefore, used in approximately 41.5% of all youth-related sexual searches.

My own analysis of the data from Google Trends found that searches including the words “teen” and “porn” account for roughly 3% of all searches that include the word “porn”, a figure that has remained relatively stable over the last ten years. So when one considers all the other possible variations on the word “teen” that could be used to search for sexual content, not to mention the wide array of variant terms that could be used to search for pornography, it’s not unreasonable to think that the figures I’ve extracted from Google Trends, which cover the period from January 2004 to March 2014, are very much in keeping with figures reported by Ogas and Gaddam and both are, of course, a long way short of the inflated “one-third of all pornographic searches” that Dines gave to the court. Porn that features youthful-looking women is certainly popular, but nothing like as popular as Dines tries to suggest and, when you crunch the numbers properly, its overall popularity seems pretty consistent both over time and across different cultures, as if to suggest that a general predilection for youth is something of a human constant, an observation that to any evolutionary psychologist must sound very much like confirmation that bears do indeed shit in the woods.

That doesn’t, however, mean that the data doesn’t have a few interesting stories to tell if only you bother to look for them.

One of the clearest trends in the data, once you start to drill down into specific niches and the data on regional traffic is that of “local porn for local people”. As you move around the globe and look at what Google’s search traffic has to say about local interests in porn you’ll find a few constants – pretty much everyone, of course, likes “free porn” – but also significant local variations. India is quite possibly the only country in the world where people are more interesting in finding Indian porn than they are free porn. Russia, Hungary, Turkey all have their own native free porn tubes which rival and, in many cases, comfortably exceed many of the big global porn tubes for popularity within those markets while there is an entire network of Central and South American porn tubes serving localised content in the largest local markets via localised domains but all using the same interface. So far I’ve managed to track down SambaPorno (Brazil), TangoPorno (Argentina), CuecaPorno (Chile) and AztecaPorno (Mexico) – I’m sensing a bit of a theme here – and there could be a few others floating around if you look hard enough, although somewhat disappointingly there doesn’t appear to be any sign of a WorkersRevolutionaryPorno to serve the Cuban and Venezuelan markets.

Elsewhere, the single most popular adult site in the Czech Republic isn’t even a free porn tube, it’s actually the main gateway to a network of local pay sites that feature exclusively local content while of the top three adult sites in the Japanese market, one delivers only local content via pay per view and monthly subscription and another is an English language “Hentai” fan site/community. Finally, let’s spare a thought or two for Pakistan where two of the top five adult sites are web proxies with a further five sites in the current top fifteen dedicated solely to unblocking access to YouTube.

Where this is taking us is towards an emerging issue in the social sciences, and in particular in psychological research, which is that most what we think we know about human behaviour is based almost exclusive on studying “WEIRD” people; Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic.

Many sciences have a standard test subject, used over and over by its practitioners. Geneticists use fruit flies, endocrinologists use guinea pigs, molecular biologists use mice. For behavioral scientists, it’s the college freshman. It’s easy to understand why: they’re cheap, in plentiful supply, easy to motivate through course requirements, and willing to endure even the most unusual experimental methods. Much of our contemporary understanding of ethics, aggression, and sexuality is based upon the behavior of adolescent psych majors. But recently, researchers have begun to wonder just how valid this understanding really is. After all, don’t undergrads— jobless, childless, and marinating in sex hormones—represent a unique specimen of Homo sapiens?

Surely there are behavioral experiments that don’t use college students? There are indeed studies that use adults, children, and retirees. But almost all of these people are still “WEIRD”: Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. A stunning 96 percent of subjects in psychology experiments from 2003 to 2007 have been WEIRD, according to Joseph Henrich, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of British Columbia, and his co-authors. But the real trouble, says Henrich, is that WEIRD people are different from the other 88 percent of the world’s population. He compared the result of studies on cooperation, learning, decision making, and even basic perception that used both WEIRD and non-WEIRD subjects. Henrich found striking differences. “The fact that WEIRD people are the outliers in so many key domains of the behavioral sciences renders them—perhaps—one of the worst subpopulations one could study for generalizing about Homo sapiens.”

Ogas & Gaddam, “A Billion Wicked Thoughts”

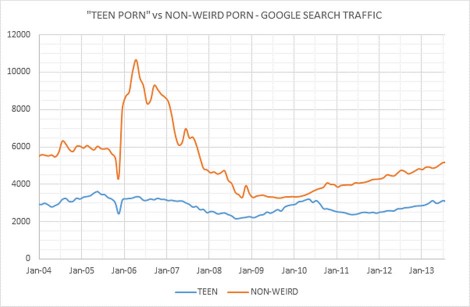

Hmm, so what happens if we pull together all the search traffic data for non-WEIRD porn and compare that to the data for “teen porn”?

This…

Figure 8. Google search trends for “teen porn” and non-WEIRD porn from January 2004 to March 2014.

We’re looking again at the normalised data so the figures here are for the number of searches per 100,000 searches containing the word “porn” and the non-WEIRD data set includes just three broad ethnic categories (Asian, Black and Latina) and five nationalities (Brazilian, Indian, Japanese, Russian and Thai). What isn’t shown on this graph, but which is crucial to making sense of the trend lines, especially the non-WEIRD trend, is any of the search traffic looking for specific porn tube site by name and what you need to know there is that the first such site to take off in a big way, YouPorn, does not even make register on Google Trends until November 2006 but by May 2008 it was generating around 5 million searches per day compared what would then have been around 11 million searches per day that contained the word “porn”.

Okay, so the story here is that right up until the end of 2005, the vast bulk of Google’s porn search traffic came from WEIRD countries in North America, Western Europe and Australasia with only one notable exception, India, which unsurprisingly led the world in searches for Indian porn. Then, from the beginning of 2006 right through to late 2007, we see both the big spike in non-WEIRD porn search traffic which coincides with the appearance for the first time of several non-WEIRD countries in Google’s search traffic data, most notably South Korea, South Africa, the Czech Republic and Turkey and the way in which it rapidly recedes over the same period in YouPorn is rising to prominence and, indeed, by second half of 2008 the numbers of people looking specifically for either “teen porn” or any of the non-WEIRD categories have fallen below the level that existed prior to 2006. From there, there’s a bit of a resurgence of interest in “teen porn” which seems to coincide with Pakistan and Kenya bubbling their way up to the top of the rankings but that quickly tails off in a manner which may suggest a bit of regression to the mean while the non-WEIRD trend remains fairly stable over the course of 2009 and then from 2010 begins to climb, albeit at a very modest rate, as Africa, South East Asia and even Oceania begin to emerge as the leading sources of porn search traffic across a number of niches, including most of the non-WEIRD categories.

So yes, a lot of people like the performers in their to appear youthful but they also clearly like them to look very much like themselves as well, and certain it’s not just people living in the non-WEIRD countries who exhibit a tendency to look for either locally produced porn or porn that features performers from their own ethnic group. It’s no coincidence at all that the US states in which “black porn” exceeds both “teen porn” and “gay porn” in popularity run along the line of the US’s “Black Belt” from Louisiana up to North Carolina and Maryland while of the nine countries for which Pornhub released data showing the top three search terms by country for 2013 – the US, UK, Germany, France, Italy, Japan, Spain, Mexico and Brazil – the only one for which a search for local porn didn’t make the top spot (or even the top three) was the United States.

The obvious inference here is that the mental leap from the globalisation of the distribution of pornography via the large porn tubes to the globalisation of a youth-obsessed American porn ‘culture’, if that can even be said to exist, is neither as straightforward nor as obvious as anti-porn campaigners like Gail Dines would have us believe. Interest in Internet pornography may be a global phenomenon – the only independent country for which Google Trends doesn’t have any kind of porn search data is, unsurprisingly, North Korea – and interest in sex is, of course, a universal feature of our species – let’s face it, I wouldn’t be here to write any of this, and you wouldn’t be here to read it, if it wasn’t – but it doesn’t automatically follow that American porn, which after all is only a reflection of American culture, will prove to be universally popular around the globe. The global culinary plague that is the MacDonald’s burger bar may very well have spread to 116 countries around the globe by the middle of 2013 but that doesn’t mean that everyone eats there or that people are losing their taste for their local cuisine.

Okay, so that wraps things up for part one. In part two I’ll be looking at the claims Dines made in court about the apparent popularity of certain types of content within the “Teen” and “MILF” sub-genres and whether or not that, again, stands up to detailed scrutiny.